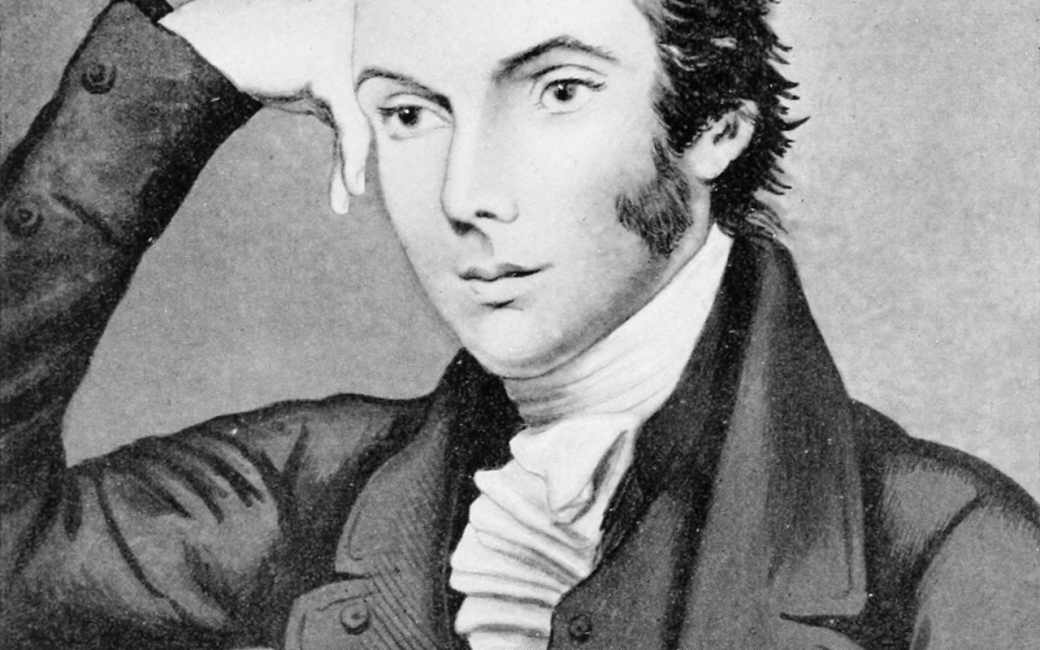

The depiction of a kneeling slave was commonly used as a banner for abolitionist groups in Great Britain.

Take notice of the gender specifications in the logos

In a previous post to this blog titled Birmingham Ladies’ Society for Relief of Negro Slaves, I briefly discussed upper class women’s groups in the 1800s, and their effect on the spread of abolition in Great Britain. In that post I presented an argument by Clare Midgley that interpreted these groups as, “kneeling enchanted women who were pathetically appealing for their freedoms.”(1) For critics like Midgley, these women’s groups had questionable impact on influencing real social and political change. This stance does find validity in the short term historical analysis of eighteenth and nineteenth century society. However, when analyzing broader scope of historical events their efforts do find greater influence.

The anti-slavery movement gave women the opportunity to take an opinionated stance in a more formal political and social forum. Many historians argue that, “the historical intersection of a feminist impulse with anti-slavery agitation helped secure white British women’s political self-empowerment.” (2) Women like Emma Courtney began to connect with the struggle behind abolition with that of emancipation.(3) The general goal of equality was shared and respected by these two groups.

While it is true that upper-class women’s groups were not actively and aggressively pushing anti-slavery ideology, their effect on a broader historical context should not be mitigated just because they were not as outspoken as some of their abolitionist counterparts. Do you agree more with Midgley’s perspective or the counter argument that was presented in this post?

~WDL

References

- Midgley, Clare. “Anti-Slavery and Feminism in Nineteenth-Century Britain.” Gender & History3(1993): 343-62. Web.

- Ferguson, Moira. Subject to Others British Women Writers and Colonial Slavery, 1670-1834. Abingdon: Routledge, 2014. Print.

- Ferguson, Subject to Others, 196.